Zamboanga.com is not just about Zamboanga

Zamboanga.com goes beyond just featuring Zamboanga City; it is a comprehensive resource about the entire Philippines. Visitors can explore detailed pages about the:

18 Regions | 82 Provinces | 149 Cities | 1493 Municipalities | 42,011 Barangays

This makes zamboanga a valuable portal for anyone wanting to discover and learn about the Philippines in its entirety. The site interacts with you. You can contribute any information to enhance any page by simply posting the data in the comment section of the page.

First, we would like to highlight Zamboanga City, the namesake of zamboanga.com. Located at the southwestern tip of the Zamboanga Peninsula in Mindanao, Zamboanga City is rich in history and culture. Founded in 1635 as a Spanish fort and trading hub, it remains a vibrant city known for its unique Chavacano language, Spanish-influenced heritage, and beautiful coastal landscapes. Often called “Asia’s Latin City,” it serves as a gateway to the diverse people, languages, and heritage found across the Philippines.

The Zamboanga Peninsula — a long, curving landmass jutting out from the western edge of Mindanao — is surrounded by the Sulu Sea to the north and west, and the Moro Gulf to the south Historically a single vast province, it was later politically subdivided into Zamboanga del Norte, Zamboanga del Sur, Zamboanga Sibugay, and the highly urbanized City of Zamboanga.

Zamboanga, the peninsula’s commercial and cultural hub, is famed for Chavacano, a Spanish‑based creole that has evolved over centuries of trade, migration, and colonial history. While Chavacano remains the dominant language in the city, it is also understood to varying degrees in surrounding provinces. In Zamboanga del Norte, Zamboanga del Sur, and Zamboanga Sibugay, daily conversation is conducted mainly in Cebuano/Bisaya, with Tagalog and English widely used in education, governance, and commerce.

This blend of languages reflects the peninsula’s diverse heritage — from the indigenous Subanen communities of the interior, to Visayan settlers from Bohol and Cebu, to Muslim coastal traders whose influence is still felt in local culture, cuisine, and traditions.

Fort pilar is the foundation of Zamboanga City and its Chavacano language.

Zamboanga traces its roots back to Fort Pilar, which also serves as the foundation for its unique Chavacano language.

Fort Pilar of Zamboanga was constructed by Spain in 1635 under the the supervision of Melchor de Vera. Fort Pilar became the check point to prevent slave traders moving their captured victims from north to south. Rajah Dalasi of Bulig Maguindanao was determined to stop the Spaniards from policing the slave trading hence 3,000 Moros made the bloody attack of the fort in December 8, 1720 (feast day of the Immaculate Conception). To this day, the Moros continue their persistent efforts to gain control over Zamboanga City. They now use the legal system, specifically through plebiscites, under the banner of the Bangsamoro.

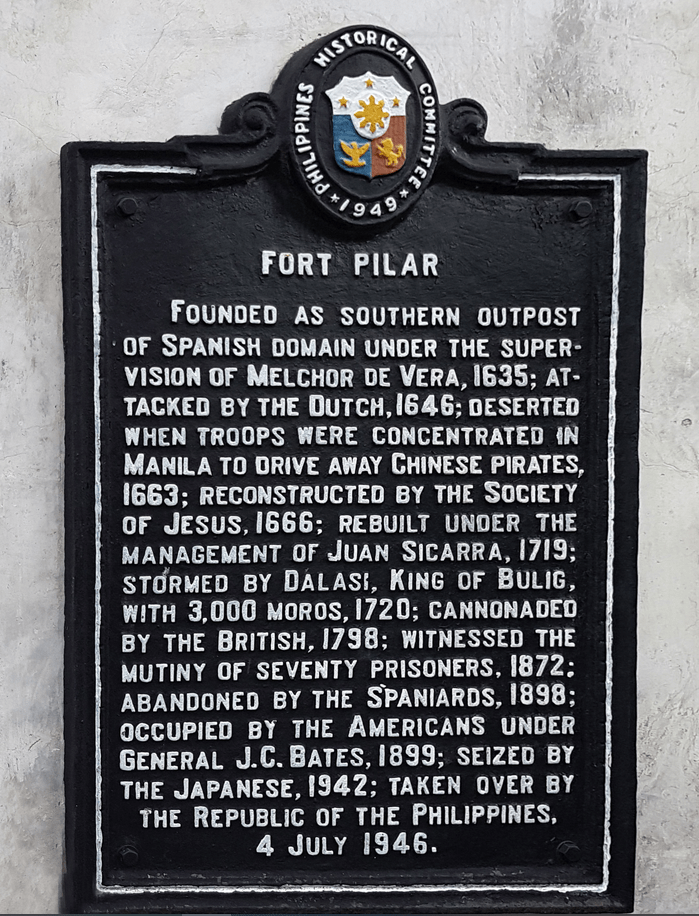

The plaque to the left: “Fort Pilar” reads as follows so you can copy paste:

“Founded as southern outpost of Spanish Domain under the supervision of Melchor de Vera, 1635; Attacked by the Dutch, 1646; Deserted when troops were concentrated in Manila to drive away Chinese pirates, 1663; Reconstructed by the Society of Jesus, 1666; Rebuilt under the management of Juan Sicarra, 1719; Stormed by Dalasi, King of Bulig, with 3,000 moros, 1720; Cannonaded by the ; British, 1798; Witnessed the mutiny of seventy prisoners, 1872; Abandoned by the Spaniards, 1898; Occupied by the Americans under General J.C. Bates, 1899; Seized by the Japanese, 1942; Taken over by The Republic of the Philippines, July 4, 1946.”

June 23, 1635 should be symbolically known as Dia del Chavacano de Zamboanga. Why you might ask? This was the day that a permanent foothold was laid on Zamboanga by the Spanish government with the construction of the San Jos Fort, and the subsequent evolution and proliferation of a unique dialect/language based on ancient Creole Spanish that is called Chavacano de Zamboanga. This is our history, this is our culture. >> Read More

Shop Maletsky Mart: Apparel | Bags & Shoes | Health and Beauty | Automotive | Electronics | Herbal | Home Improvement | Jewelry | Pets | Children & ToysSearch for Products below.

The Republic of Zamboanga

The entire Zamboanga Peninsula was under the name of Zamboanga and was even once the Republic of Zamboanga for a brief period of time.

Republic of Zamboanga (Revolutionary Government of Zamboanga): May 18, 1899 – Nov 16, 1899 (de facto) – This was the timeline when the new republic was independent and free of any foreign influence.

May 18, 1899 – Fort Pilar and its Spanish troops, in Southern Philippines, surrendered to the Revolutionary Government of Zamboanga.

May 23, 1899 – The Spaniards evacuate the city of Zamboanga for good, after burning down most of the city’s buildings in contempt of the Zamboangueños’ revolt against them.

May 23, 1899 – The Spaniards evacuate the city of Zamboanga for good, after burning down most of the city’s buildings in contempt of the Zamboangueños’ revolt against them.President of Zamboanga Republic

May 18, 1899 to November 16, 1899 [barely six (6)months], Vicente S. Alvarez was chosen by his fellow Zamboangueños to be their first president and popular leader of the revolutionary government established immediately after the former Spanish garrison troops evacuated to Manila. The events that followed afterwards were historically described as a mob mentality, filled with divided partisanship that lent to “jealous self-interest, biter rivalry, rapacity, and bloodshed” from assassinations and cattle-shooting for amusement. The president and his fellow Christian Zamboangueños’ actions could not be considered heroic by any means, but was paralleled with that of the Moro Pirates with whom the fort of Real Fuerza de Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Zaragosa was erected to defend against.

The rivalry between the local revolutionary leadership of President Vicente S. Alvarez and opposition leader Isidoro Midel allowed for the easy subjugation of the city by the American forces when Midel sided with the Americans upon their arrival. As a reward for his help, the new American rulers allowed Isidoro Midel to continue as president of the new Zamboanga Republic for about sixteen (16) months, against the will of the people, after former president Vicente S. Alvarez fled to Mercedes, then later to Basilan, when the Americans arrived and took control of the fort del Pilar and its remaining armament. The saying “divide and conquer” was aptly applied to the new Zamboanga Republic.6 Read more…

Chartered City of Zamboanga

(“Solemn act of the signing by the President of the Philippines of the Organic Law creating the City of Zamboanga. Malacañang Palace, Manila, October 12, 1936.”) The inscription on the picture. Zamboanga City became an independent Chartered City and ceased to be under the jurisdiction of the Provincial Government of Zamboanga on October 12, 1936, when President Manuel P. Quezon signed the Charter as history commemorates it, in this historical photograph taken in October 12, 1936 in Malacañang Palace, Manila, Philippines, during the official signing ceremony of the Charter of Zamboanga City. The event was witnessed by the charter bill author Congressman Juan S. Alano and wife Ramona, and other notable Zamboanguenos. The mayor of Zamboanga City at that time was : Antonio Toribio – 1934-1937 The assemblyman of Zamboanga Province to the National Assembly of the Philippine Commonwealth was: Juan S. Alano – (1936-1941)

The photo above shows that the charter of Zamboanga City was Signed by the President of the Philippines (Manuel P. Quezon – Sitting) on October 12, 1936

Left to Right Standing:

- name of #1

- (Vicente C. Suarez?)

- name of #3

- name of #4

- (Agustin L. Alvarez?)

- (Nicasio S. Valderrosa?)

- Don Pablo R. Lorenzo, Zamboanga Mayor 1939-1940; Zamboanga delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1934.

- Congressman Juan S. Alano

- Ramona Alano, wife of Congressman Juan S. Alano

- Maria Clara Lorenzo Lobregat who later in life became a congress woman and mayor of Zamboanga City, Philippines.

- (Santiago Artiaga?)

- Probably the mayor and Assemblyman were here during the signing. If you recognize them, please point them out.

NOTE: If you know any of these people in this historical photo of Zamboanga City’s creation, please email the information to franklin_maletsky@yahoo.com Thank you.

Zamboanga City is a chartered city (established October 12, 1936) and is an independent component not part of any province in the Philippines. It is the 6th most populated city in the Philippines and, with a total land area of 1,483.38 square kilometers, it ranks as the 3rd largest city in the country.

Zamboanga City is known as the “urgullo de Mindanao” and was originally called the City of Flowers. Later, the Lobregat family lobbied to change the tagline to “Asia’s Latin City.” Often called the Pride of Mindanao, Zamboanga City is located at the tip of the Zamboanga Peninsula and is one of Mindanao’s major cities.

Historically, Zamboanga City was the capital of Zamboanga Province. On October 12, 1936, it became a chartered city and was carved out from the province, but it remained its capital. Then, on September 17, 1952, through Republic Act No. 711, Zamboanga del Sur and Zamboanga del Norte were created by partitioning the original province, effectively dissolving the Zamboanga Province.

As the Zamboanga Peninsula flourished, it was later divided into five major areas: Zamboanga City, Zamboanga del Norte, Zamboanga del Sur, Zamboanga Sibugay, and Misamis Occidental.

The prosperity of the Zamboanga region heavily depends on highways connecting all its provinces, municipalities, and cities. Within these areas, farm-to-market roads are continually being constructed and improved. By 2030, people will be able to travel from Oroquieta City to Zamboanga City without having to pass through Zamboanga del Sur or Sibugay.

With the infrastructure in place, prosperity is sure to follow.

Zamboanga’s continuing battle with the national government

Zamboanga City is in Region IX(9) but is NOT a part of Zamboanga del Sur. The Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG), National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB), Commission on Election (comelec), PIA (Philippine Information Agency), and the office of the president of The Philippines as of today (01/11/2024), continues to incorrectly lists Zamboanga City as part of Zamboanga del Sur. You will notice that even google maps shows zamboanga city as part of zamboanga del sur.

The Zamboangueños

People who live in Zamboanga City are called Zamboangueños. The majority of the people who live in Zamboanga City speak the chavacano language. Of course several other languages are spoken in Zamboanga City but the local residents are really proud of their language and the name that they have coined it, “chavacano”.

Chavacano is the unique native language (dialect) of the Zamboangueños, a mixture of Spanish and various other local dialects and international languages, and is one of the oldest spoken language in the country reflecting a rich linguistic history of its people. English is widely spoken around town, and is the main language of education and international commerce. Numerous international languages, like German, Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, Italian, and Spanish, are spoken here, giving light to its historical importance as an international investment and destination haven for over three-hundred years.

Some refer to the language as ‘chabacano’, which the Zamboangueños don’t mind, as some of them use ‘chabacano’ interchangeably with ‘chavacano’. However, it’s commonly accepted that if you’re officially referring to the language of the Zamboangueños, it’s best to call it ‘chavacano’. Many Zamboangueños pronounce the letter “V” as “B”, the “F” as “P”, and the “Z” as “S”. For instance, they might say ‘chabacano’ but write it as ‘chavacano’, or say ‘prio’ but write ‘frio‘, or pronounce ‘crus’ but write it correctly as ‘cruz‘.

Zamboanga’s Real History: From Ancient Samboangan to Fort Pilar

Long before it became Zamboanga City, this coastal region of Mindanao was known as Samboangan (also spelled Sambuwangan). The name comes from the Subanen/Subanon word samboang, meaning “mooring pole” — wooden stakes used for tying boats along the shore. This made sense: the area served as a natural docking point for traders from China, Borneo, the Malay archipelago, and nearby Philippine islands.

For centuries, Samboangan functioned as an active trade center where people exchanged rice, beeswax, metal tools, ceramics, pearls, forest products, and woven cloth. The earliest inhabitants of the peninsula, the Subanen people, controlled river routes, inland access, and much of the agricultural trade.

Subanen Life: Early Farmers and River Traders

Archaeological finds across the Zamboanga Peninsula — including stone tools, imported ceramics, and beads — show that Subanen communities existed here for thousands of years. They lived along rivers in bamboo houses with cogon roofs, growing rice, root crops, bananas, and abaca. Their villages were governed by timuay (leaders) and councils of elders, practicing cooperation rather than centralized rule. Land ownership was collective; no individual claimed total control.

The Subanen traded actively with seafaring groups like the Sama-Bajau, who expanded through the Sulu Sea and Mindanao coasts between 1200–1300 AD. Trade was conducted almost entirely through barter. The discovery of Chinese jars, Southeast Asian ceramics, and Indian beads confirms that Samboangan was deeply connected to regional commerce before the Spanish era.

Datu N’wang in Subanen Oral Tradition

Subanen elders tell stories of a leader named Datu N’wang (or Nawang), remembered as a timuay or “Keeper” of early Samboangan. According to these oral histories:

- He lived near the coastal trading grounds.

- He settled disputes under a large balete tree facing the sea.

- He welcomed incoming boats and managed market order.

- His brothers were said to oversee nearby regions — one north toward Sindangan and one south toward Labangan.

These accounts reflect the Subanen tradition of shared leadership and community-based governance.

However, it is important to clarify:

Datu N’wang does not appear in surviving Spanish records or archaeological documents. His story survives through Subanen oral tradition, not formal historiography.

Even so, his presence in local memory enriches the cultural narrative of pre-colonial Samboangan.

Spain Arrives: The La Caldera Attempts (1569 & 1596–1599)

Although Spain reached the Philippines in 1521, they did not attempt firm control of Zamboanga until decades later. Their interests included securing trade routes, countering local sultanates, and controlling maritime movement in the Sulu Sea.

1569 – First La Caldera Settlement

A small Spanish mission and garrison were built at La Caldera (modern Barangay Recodo, Zamboanga City). Due to limited manpower and persistent attacks, the post was abandoned quickly.

1596–1599 – Second La Caldera Presidio

In 1596, Captain Juan Ronquillo established a stronger Spanish garrison at La Caldera, the area that corresponds today to Barangay Recodo, Zamboanga City. Captain Juan Pacho commanded about 100 soldiers, but the fort faced continuous resistance from Tausug and other regional warriors.

By 1598, Pacho and twenty of his men were killed in battle. The Spaniards abandoned and burned the presidio by 1599, and Spanish control disappeared again.

For nearly four decades, Samboangan remained under indigenous and maritime influence.

Permanent Spanish Occupation: 1635

Spain returned with greater force. On April 6, 1635, Captain Juan de Chaves landed with Spanish troops and more than a thousand Visayan auxiliaries, establishing a permanent settlement at Samboangan — the very bayfront associated with trading activity in Subanen stories.

This marked the beginning of colonial Zamboanga. The Spanish spelling “Zamboanga” replaced the earlier “Samboangan.”

Fort Pilar: Birth of a Colonial Stronghold

On June 23, 1635, Father Melchor de Vera, a Jesuit priest-engineer, laid the cornerstone of the fortress:

Real Fuerza de Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Zaragoza

(now known simply as Fort Pilar).

The fort’s purpose was clear:

- defend against Moro maritime raids

- protect Spanish shipping lanes

- expand missionary activity into Mindanao

- establish a forward military base for the Spanish Crown

Fort Pilar became the center of Spain’s presence in western Mindanao. Although the Spaniards temporarily abandoned it in 1662 (due to threats from Chinese pirate Koxinga in Luzon), they returned and maintained control for centuries afterward.

Impact on the Subanen People

Spanish expansion redefined the region. Rivers and fertile lowlands were taken for settlements, missions, and agriculture. Subanen communities were gradually pushed into upland areas, where many remained isolated.

Despite missionary pressure, forced labor systems, and colonial taxation, Subanen culture survived. Their oral histories — including the stories of leaders like Datu N’wang — continued to pass from generation to generation, preserving their identity and memory of pre-colonial Samboangan.

Today, Fort Pilar stands not only as a colonial monument but as a reminder of the transformation from a free indigenous port to a fortified Spanish outpost.

Timeline Summary

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| Neolithic Period | Earliest Subanen settlement in the Zamboanga Peninsula |

| Pre-1300 AD | Samboangan develops as a coastal trading hub |

| 1569 | First Spanish attempt at La Caldera (Recodo) |

| 1596–1599 | Second presidio established and later abandoned |

| April 6, 1635 | Juan de Chaves establishes permanent Spanish settlement |

| June 23, 1635 | Construction of Fort Pilar begins |

Some English to Chavacano Words:

Blessed, in Chavacano or chabacano is: Bendecido

Blessed in Chavacano or Chabacano is: Bendecido Alternate chavacano word: Alternate English word for “Bendecido” is Note: List…

Table, in Chavacano or chabacano is: Mesa

Table in Chavacano or Chabacano is: Mesa Alternate chavacano word: Alternate English word for “Mesa” is Note: List…

Blade, in Chavacano or chabacano is: Pilo

Blade in Chavacano or Chabacano is: Pilo Alternate chavacano word: Alternate English word for “Pilo” is Note: List…

Featured Local Government Unit of the Philippines

Balungag, San Fernando, Cebu

Balungag is a barangay of San Fernando in the Cebu within Region 7 (Central Visayas), Philippines. >>> Click to go…

San Agustin, Gandara, Samar (Western Samar)

San Agustin is a barangay of Gandara, Samar (Western Samar) in the province of Samar (Western) within Region 8 (Eastern…

Featured News of the Philippines

The Next 5 Years: AGI Will Unlock the Universe and Your Data

Revolutionize Our Understanding of the Cosmos

Humanity’s quest to understand the cosmos has driven some of the most extraordinary scientific and technological achievements in history. Over decades, satellites, space telescopes such as Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and deep-space probes like Voyager 1 and 2 have collected vast volumes of data on galaxies, black holes, exoplanets, and cosmic phenomena billions of light-years away.

The Astronomical Data Backlog: An Untapped Treasure Trove of Secrets

Despite the remarkable efforts made by space agencies and observatories worldwide, the astronomical data collected far exceeds our current capacity to process it fully. Managing and analyzing these datasets has become a gargantuan challenge. To put it in perspective:

- Hubble has captured over 1.5 million observations since its launch in 1990.

- JWST alone generates terabytes of data every day, streaming unprecedented detail about the early universe.

- Ground-based radio telescopes and satellite dishes around the globe continuously record signals, many stored for future analysis.

Many of these data — including historical archives spanning decades — remain partially or completely unprocessed. Researchers estimate that fully analyzing all existing cosmic data could take years, if not decades. This delay potentially keeps many groundbreaking discoveries hidden, unable to contribute to our understanding of the universe.