LOG IN. UPLOAD PICTURES.

The Philippines has Zambo Mart to help propagate the Chavacano Language.

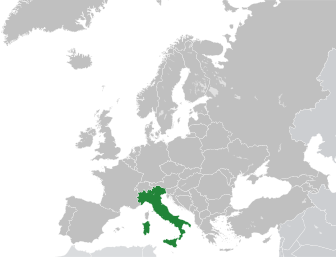

Italy

Rome • Milan • Naples • Turin • Palermo • Genoa • Bologna • Florence • Catania • Bari • Venice • Verona • Messina • Padua • Padova •

|

|

Location of Italy within the continent of Europe | |||

Map of Italy | |||

Flag Description of Italy:The flag of Italy was officially adopted on January 21, 1919. The modern Italian flag, the famous tricolore, is derived from an original design by Napoleon. It consists of three vertical bands of equal width, displaying the national colors of Italy: green, white and red. Green was said to be Napoleon's favorite color. | |||

|

Official name Repubblica Italiana (Italian Republic)

Form of government republic with two legislative houses (Senate [3231]; Chamber of Deputies [630])

Head of state President: Giorgio Napolitano

Head of government Prime Minister: Matteo Renzi

Capital Rome

Official language Italian2

Official religion none

Monetary unit euro (€)

Population (2013 est.) 59,866,000COLLAPSE

Total area (sq mi) 116,346

Total area (sq km) 301,336

Urban-rural population

- Urban: (2011) 68.4%

- Rural: (2011) 31.6%

Life expectancy at birth

- Male: (2011) 79.4 years

- Female: (2011) 84.5 years

Literacy: percentage of population age 15 and over literate

- Male: (2007) 99.1%

- Female: (2007) 98.6%

GNI per capita (U.S.$) (2012) 33,840

1Includes 7 nonelective seats (5 presidential appointees and 2 former presidents serving ex officio).

2In addition, German is locally official in the region of Trentino–Alto Adige, and French is locally official in the region of Valle d’Aosta.

Background of Italy

To the north, Italy borders France, Switzerland, Austria, and Slovenia, and its borders are largely naturally defined by the Alpine watershed. To the south, it consists of the entirety of the Italian Peninsula and the two largest Mediterranean islands of Sicily and Sardinia as well as around 68 smaller islands. There are two small independent states within Italy: the Vatican City in Rome, and the Republic of San Marino. The most important sectors of Italy’s economy in 2012 were wholesale and retail trade, transport, accommodation and food services (20.6 %) and industry (18.4 %) and public administration, defence, education, human health and social work activities (16.9 %). Italy’s main export partners are Germany, France and the US while its main import partners are Germany, France and China.

Geography of Italy

The Land

To the north the Alps separate Italy from France, Switzerland, Austria, and Slovenia. Elsewhere Italy is surrounded by the Mediterranean Sea, in particular by the Adriatic Sea to the northeast, the Ionian Sea to the southeast, the Tyrrhenian Sea to the southwest, and the Ligurian Sea to the northwest. Areas of plain, which are practically limited to the great northern triangle of the Po valley, cover only about one-fifth of the total area of the country; the remainder is roughly evenly divided between hilly and mountainous land, providing variations to the generally temperate climate.

Relief

Mountain ranges higher than 2,300 ft (702 m) occupy more than one-third of Italy. There are two mountain systems: the scenic Alps, parts of which lie within the neighbouring countries of France, Switzerland, Austria, and Slovenia; and the Apennines, which form the spine of the entire peninsula and of the island of Sicily. A third mountain system exists on the two large islands to the west, Italian Sardinia and French Corsica.

MOUNTAIN RANGES

The Alps run in a broad west-to-east arc from the Cadibona Pass, near Savona on the Gulf of Genoa, to north of Trieste, at the head of the Adriatic Sea. The section properly called Alpine is the border district that includes the highest masses, made up of weathered Hercynian rocks, dating from the Carboniferous and Permian periods (approximately 360 million to 250 million years ago). The Alps have rugged, very high peaks, reaching more than 12,800 ft (3,900 m) in various spectacular formations, characterized as pyramidal, pinnacled, rounded, or needlelike. The valleys were heavily scoured by glaciers in the Quaternary Period (the past 2.6 million years); there are still more than 1,000 glaciers left, though in a phase of retreat, more than 100 having disappeared in the past half century or so.

The Alpine mountain mass falls into three main groups. First, the Western Alps run north to south in Italy from Aosta to the Cadibona Pass, with Mount Viso (12,602 ft [3,841 m]) and Gran Paradiso (13,323 ft [4,061 m]), regarded as the highest mountain wholly within Italy, both base and peak. Second, the Central Alps run west to east from the Western Alps to the Brenner Pass, leading into Austria and the Trentino–Alto Adige valley, also with high peaks, such as Mont Blanc (with a summit just over the border in France of 15,771 ft [4,807 m]), the Matterhorn (Italian Monte Cervino; 14,692 ft [4,478 m]), Monte Rosa (with a summit just over the border in Switzerland of 15,203 ft [4,634 m]), and Mount Ortles (12,812 ft [3,905 m]). Lastly, the Eastern Alps run west to east from the Brenner Pass to Trieste and include the Dolomites (Dolomiti; see photograph) and Mount Marmolada (10,968 ft [3,343 m]). The Italian foothills of the Alps, which reach no higher than 8,200 ft (2,500 m), lie between these great ranges and the Po valley. They are composed mainly of limestone and sedimentary rocks. A notable feature is the karst system of underground caves and streams that are especially characteristic of the Carso, the limestone plateau between the Eastern Alps and southwestern Slovenia.

The Apennines are the long system of mountains and hills that run down the Italian peninsula from the Cadibona Pass to the tip of Calabria and continue on the island of Sicily. The range is about 1,245 miles (2,000 km) long; it is only about 20 miles (32 km) wide at either end but about 120 miles (190 km) wide in the Central Apennines, east of Rome, where the “Great Rock of Italy” (Gran Sasso d’Italia) provides the highest Apennine peak (9,554 ft [2,912 m]) and the only glacier on the peninsula, Calderone, the southernmost in Europe. The Apennines comprise predominantly sandstone and limestone marl (clay) in the north; limestone and dolomite (magnesium limestone) in the centre; and limestone, weathered rock, and Hercynian granite in the south. On either side of the central mass are grouped two considerably lower masses, composed in general of more recent and softer rocks, such as sandstone. These sub-Apennines run in the east from Monferrato to the Gulf of Taranto and in the west from Florence southward through Tuscany and Umbria to Rome. This latter range is separated from the main Apennines by the valleys of the Arno and the Tiber rivers. At the outer flanks of the sub-Apennines, two allied series of limestone and volcanic rocks extend to the coast. They include, to the west, the Apuane Alps, which are famous for their marbles; farther south, the Metallifere Mountains (more than 3,380 ft [1,030 m]), abundant in minerals; then various extinct volcanoes occupied by crater lakes, such as that of Bolsena; then cavernous mountains, such as Lepini and Circeo, and the partially or still fully active volcanic group of the Flegrei Plain and Vesuvius; and finally the limestone mountains of the peninsulas of Amalfi and Cilento. The extensions on the Adriatic coast are simpler, comprising only the small promontory of Mount Conero, the higher peninsula of Gargano (3,465 ft [1,056 m]), and the Salentina Peninsula in Puglia. All these are limestone.

In Sardinia there are two mountain masses, separated by the long plain of Campidano, which runs from the Gulf of Asinara southeastward across the island to the Gulf of Cagliari. The group in the southwest is small and low, formed from sediment, mostly mineralized, perhaps early in the Paleozoic Era (about 540 million to 250 million years ago). The northeastern mass reaches an elevation of more than 6,000 ft (1,830 m) at Gennargentu; the underlying foundation is basically metamorphic (heat- and pressure-altered) rock, and it is covered in the northeast by Paleozoic granite and partially covered in the northwest by Mesozoic limestones (those formed about 250 to 65 million years ago) and by sandstone and clays of the Paleogene and Neogene periods (about 65 to 2.6 million years ago). There are caves on the seacoast and inland where limestones predominate.

Present volcanic action had its origins in the Pliocene Epoch (about 5.3 to 2.6 million years ago) and the Quaternary Period (the past 2.6 million years) and is represented by the Flegrei Plain, near Naples, and by the neighbouring islands, such as Ischia; by Vesuvius; by the Eolie, or Lipari, Islands; and by Mount Etna, which is on the island of Sicily. Phenomena that are related to volcanism include thermal springs in the Euganei Hills, vulcanelli (mud springs) at Viterbo, and emissions of gas at Pozzuoli.

Seismic activity, leading to earthquakes, is rare in the Alps and the Po valley; it is infrequent but occasionally strong in the Alpine foothills; and it may be catastrophic in the central and southern Apennines (as in 1980) and on Sicily.--->>>>>Read On.<<<<

Demography of Italy

The people

- Ethnic groups

Italians cannot be typified by any one physical characteristic, a fact that may be explained by the past domination of parts of the peninsula by different peoples. The Etruscans in Tuscany and Umbria and the Greeks in the south preceded the Romans, who “Latinized” the whole country and maintained unity until the 5th century. Jews arrived in Italy during the Roman Republic, remaining until the present day. With the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, Italy suffered invasions and colonization, which inevitably affected its ethnic composition. With some exceptions, the north was penetrated by Germanic tribes crossing the Alps, while the south was colonized by Mediterranean peoples arriving by sea. The Byzantines were dominant in the south for five centuries, coinciding with the supremacy of the Lombards (a Germanic tribe) in Benevento and other parts of the mainland. In the 9th century Sicily was invaded by the Saracens, who remained until the Norman invasion in the early 11th century. The Normans were succeeded by the Aragonese in 1282; in 1720 Sicily came under Austrian rule. This mixed ethnic heritage explains the smattering of light-eyed, blond Sicilians in a predominantly dark-eyed, dark-haired people. Except for the Saracen domination, the Kingdom of Naples, which formed the lower part of the peninsula, had a similar experience, whereas the northern part of Italy, separated from the south by the Papal States, was much more influenced by the dominant force of the Austrians. The Austrian admixture, combined with the earlier barbarian invasions, may account for the greater frequency of light-eyed, blond Italians originating in the north. The ethnic mixing continues to the present day. Since the 1970s, Italy has been receiving immigrants from a number of less-developed countries. A predominantly female migration from the Philippines and other Asian countries compares with a predominantly male influx from North Africa. With the accession of numerous former Soviet-bloc countries to the European Union in 2004 and 2007, immigration from eastern Europe soared. In the early 21st century about five million foreigners—roughly half of them from eastern Europe—resided on Italian territory.

- Languages

Standard Italian, as a written administrative and literary language, was in existence well before the unification of Italy in the 1860s. However, in terms of spoken language, Italians were slow to adopt the parlance of the new nation-state, identifying much more strongly with their regional dialects. Emigration in the late 19th and early 20th century played an important role in spreading the standard language; many local dialects had no written form, obliging Italians to learn Italian in order to write to their relatives. The eventual supremacy of the standard language also owes much to the advent of television, which introduced it into almost every home in the country. The extremely rich and, hitherto, resilient tapestry of dialects and foreign languages upon which standard Italian has gradually been superimposed reveals much about Italy’s cultural history. Not surprisingly, the greatest divergence from standard Italian is found in border areas, in the mountains, and on the islands of Sicily and Sardinia.

Only a few languages spoken in limited geographic areas enjoy any legal protection or recognition. These are French, in Valle d’Aosta; German and the Rhaetian dialect Ladino in some parts of the Trentino–Alto Adige; Slovene in the province of Trieste; Friulian (another Rhaetian dialect) and Sardinian, spoken by the two largest linguistic minorities in Italy, received official recognition in 1992. Linguistic minorities persisting in the Alps are, broadly speaking, the result of migratory movements from neighbouring countries or changes in the borderline. The French and Franco-Provençal spoken in Valle d’Aosta date from union with Savoy, but the German spoken in the same area dates from the 12th-century emigration of German sheepherders from the upper valleys of the Rhône. The German spoken in the Trentino–Alto Adige dates back to Bavarian occupation in the 5th century, whereas that spoken in the provinces of Verona and Vicenza dates from a more recent colonization in the 12th century. Some of the Alpine areas have such a complex linguistic makeup that precise measurement of linguistic communities is impossible. In Friuli–Venezia Giulia, for example, many communes are bi-, tri-, and even quadrilingual, as in the case of Canale, where Slovene, Italian, German, and Friulian coexist. In certain Occitan-speaking parts of Piedmont, Italian is the official language, Occitan is spoken at home, and the Piedmontese dialect is used in trading relations with people from lowland areas. Farther south, in Abruzzo, Basilicata, Calabria, Puglia, and Sicily, isolated linguistic communities persist against the odds. A dialect of Albanian known as Arbëresh is spoken by the descendants of 15th-century Albanian mercenaries; Croatian, the smallest minority language, spoken by some 2,000 people, has survived in splendid isolation in Campobasso province in Molise; and Greek, or “Grico” (of uncertain origin), may be heard in two areas in Calabria and Puglia. Catalan, too, has survived in the town of Alghero in the northwest of Sardinia, dating from the island’s capture by the crown of Aragon in 1354.

- Religion

Roman Catholicism has played a historic and fundamental role in Italy. It was the official religion of the Italian state from 1929, with the signing of the Lateran Treaty, until a concordat was ratified in 1985 that ended the church’s position as the state religion, abolished compulsory religious teaching in public schools, and reduced state financial contributions to the church. More than four-fifths of the population declare themselves Roman Catholics, although the number of practicing Catholics is declining. An estimated 450,000 people worship in the Protestant church, including Lutherans, Methodists, Baptists, and Waldensians. They are all members of the Federation of Evangelical Churches in Italy (Federazione delle Chiese Evangeliche in Italia) founded in 1967. Albanian communities in two dioceses and one abbey in the Mezzogiorno practice the Eastern Orthodox rite. Migration that began in the latter third of the 20th century brought with it many people of non-Christian religious beliefs, significantly Muslims, who number more than one million. The Jewish community fluctuated between 30,000 and 47,000 throughout the 20th century. In 1987 Jews obtained special rights from the Italian state allowing them to abstain from work on the Sabbath and to observe Jewish holidays.

- Traditional regions

Italy is divided into 20 administrative regions, which correspond generally with historical traditional regions, though not always with exactly the same boundaries. A better-known and more general way of dividing Italy is into four parts: the north, the centre, the south, and the islands. The north includes such traditional regions as Piedmont, which is characterized by some French influence and was the seat of united Italy’s former royal dynasty; Liguria, extending southward around the Gulf of Genoa; Lombardy, which has long been noted for its productive agriculture and vigorously independent city communes and now for its industrial output; and Veneto, once the territory of the far-flung Venetian empire, reaching from Brescia to Trieste at its greatest extent. The centre includes Emilia-Romagna, with its prosperous farms; the Marche, on the Adriatic side; Tuscany and Umbria, celebrated for their vestiges of Etruscan civilization and Renaissance traditions of art and culture; Latium (Lazio), which contains the Campagna, whose beautiful hills encircle the “Eternal City” of Rome; and the Abruzzo and Molise, regions of the highest central Apennines, which used to support a wild and remote people. The south, or Mezzogiorno, includes Naples and its surrounding fertile Campania; the region of Puglia, with its great plain crossed by oleander-bordered roads leading to the low Murge Salentine hills and the heel of Italy; and the poorer regions of Basilicata and Calabria. On the islands of Sicily and Sardinia are people who take pride in holding themselves apart from the inhabitants of mainland Italy. However, the south and the islands have changed a great deal since about 1960 and have become more modernized. Within these four main divisions, the variety of the much smaller traditional districts is very great and depends on history as well as on topography and economic conditions.

- Settlement patterns

- RURAL AREAS

In general, rural life is in decline. The majority of the population of Italy live in cities and villages; only a fraction live in hamlets or in isolated houses. In the long Alpine valleys the economy was always both agricultural and commercial, with towns such as Aosta and Bolzano at the outlets of the lateral valleys and agricultural settlements higher up or on the slopes of hills. The perpetual subdivision of landholdings makes a purely agricultural economy precarious in this region except in the upper Adige, where the Germanic system of primogeniture survived, producing the masi, family holdings that are passed on to the eldest son intact. These rural areas now also include an increasing number of skiing and tourist centres, such as Courmayeur and Cortina d’Ampezzo. In the band of Alpine and Apennine foothills, the villages, often situated on the knolls and flanks of the hills, are linked by roads that hold to the heights, away from the humid valley floors. Each village is usually grouped around a church, a castle, or a nobleman’s palace, with its fields on the slopes around it and woodlands lower down. There are innumerable plum and cherry orchards and, above all, vineyards; their wines (Conegliano and Monferrato) are famous. Lombardy is the only area in which the ancient rural way of life has been comprehensively displaced by the development of heavy industry. The Padano-Venetian-Emilian plain is the most important agricultural and stockbreeding region of Italy. The upland plain hosts the great industrial centres such as Turin, Milan, and Busto Arsizio, while the lowland plain remains socially as well as economically rural.

Villages high in the Apennines are less prosperous than those of similar elevation in the Alps. They are still isolated, the ground is infertile, and land is rarely owned by those who work it. Tourism and the expansion of cottage craft industries, such as the porcelain making at Gubbio, near Perugia, have helped these towns survive. The lower hills and plains of Italy are covered with agricultural villages in which a wide variety of crops and vegetables are grown, though often in low yield. In Puglia and Basilicata large farms are staffed by labourers who live in urban centres, such as Cerignola and Altamura, and travel to work in the countryside. Some fertile and well-watered plains, such as the Neapolitan countryside, have a high level of productivity, especially of market vegetables. Here there is direct ownership of land and fairly dense settlement. In Sicily, settlement is clustered in widely spaced, nucleated towns, with extensive pastureland and farming. In Sardinia the settlement is sparse and mainly inland, and most of the local fishing industry is carried on by men from the mainland.

- URBAN CENTRES

Italian cities vary greatly in terms of population, economic activities, and cultural traditions. Many of them have developed close economic links with surrounding communities, forming major metropolitan areas, such as Rome, Milan, Naples, and Palermo. Slightly less populous are the urban centres of Genoa-Savona, Bologna, Catania, Messina–Reggio di Calabria, Cagliari, and Trieste-Monfalcone. The geographic pattern shows an even distribution of large metropolitan areas across the whole country, while medium-sized cities are more numerous in the north than in the south, where there is a concentration of small towns.

Historically, the location of Italian urban centres played a central role in their economic development. In the Po valley, cities such as Milan, Pavia, and Cremona were well placed for commerce, being situated at the confluence of roads or rivers. Another group of cities were those on the coast, at the mouths of rivers, or on lagoons protected by sandbars; these included Savona, Genoa, Naples, Messina, Palermo, Ancona, and Venice. At present the most economically viable urban centres are those able to engage in global trade, such as Milan, and medium-sized centres such as those in northern Tuscany that engage in light manufacturing.

Throughout the centuries, Italy’s population curve has undergone many changes, often in parallel development with population trends in other European countries. The mid-14th-century plague reduced the peninsula’s population considerably, and a long period of population growth ended at the beginning of the 17th century. From the early 18th century until unification in the 1860s, a slight, steady growth prevailed, although it was interrupted during the Napoleonic Wars. From the latter half of the 19th century to the latter half of the 20th century, the population more than doubled, despite high levels of emigration. Interestingly, the natural population increase was frequently highest during the decades of highest emigration, although there is no obvious causal relationship between the two.--->>>>>Read On.<<<<

Economy of Italy

An overview The Italian economy has progressed from being one of the weakest economies in Europe following World War II to being one of the most powerful. Its strengths are its metallurgical and engineering industries, and its weaknesses are a lack of raw materials and energy sources. More than four-fifths of Italy’s energy requirements are imported. Nonetheless, the chemical sector also flourishes, and textiles constitute one of Italy’s largest industries. A strong entrepreneurial bias, combined with liberal trade policies following the war, enabled manufacturing exports to expand at a phenomenal rate, but a cumbersome bureaucracy and insufficient planning hindered an even economic development throughout the country. Services, particularly tourism, are also very important. At the end of the 20th century, Italy, seeking balance with other EU nations, brought its high inflation under control and adopted more conservative fiscal policies, including sweeping privatization.

Although the Italian economy was a relative latecomer to the industrialization process, business in the north of the country caught up with and overtook many of its western European neighbours. Southern Italy, however, lagged behind. The percentage of the labour force working in agriculture is often taken as an indication of the rate of industrialization and wealth of a nation, and in Italy’s case the figures clearly illustrate the grave imbalances existing between north and south. Against an EU average of 4.7 percent in 2008, 3.6 percent of the Italian population worked on the land, with as many agricultural labourers from the 8 regions in the south as from the 12 regions in the north and centre. Calabria and Basilicata have the largest concentrations of farm labourers.

Although Italy is not self-sufficient agriculturally, certain commodities form an important part of the export market. Notably, the country is a world leader in olive oil production and a major exporter of rice, tomatoes, and wine. Cattle raising, however, is less advanced; meat and dairy products are imported.

- PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SECTORS

The Italian economy is mixed, and until the beginning of the 1990s the state owned a substantial number of enterprises. At that time the economy was organized as a pyramid, with a holding company at the top, a middle layer of financial holding companies divided according to sector of activity, and below them a mass of companies operating in diverse sectors, ranging from banking, expressway construction, media, and telecommunications to manufacturing, engineering, and shipbuilding. One example, the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction (Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale; IRI), set up in 1933 and closed in 2000, was a holding company that regulated public industries and banking. Many of those companies were partly owned by private shareholders and listed on the stock exchange. By the 1980s moves had already been made to increase private participation in some companies. The most notable examples were Mediobanca SpA, Italy’s foremost merchant bank, with shareholdings in major industrial concerns; Alitalia, the national airline, which filed for bankruptcy protection in 2008 before being sold to a private investment group; and the telecommunications company Telecom Italia SpA, which was created in 1994 through the merger of five state-run telecommunications concerns. Many other banks were also partially privatized under the Banking Act of 1990.

In 1992 a wide privatization program began when four of the main state-controlled holding companies were converted into public limited corporations. The four were the IRI, the National Hydrocarbons Agency (Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi; ENI), the National Electrical Energy Fund (Ente Nazionale per l’Energia Elettrica; ENEL), and the State Insurance Fund (Istituto Nazionale delle Assicurazioni; INA). Other principal agencies include the Azienda Nazionale Autonoma delle Strade Statali (ANAS), responsible for some 190,000 miles (350,000 km) of the road network, and the Ente Ferrovie dello Stato (FS; “State Railways”), which controls the majority of the rail network.

The private sector was once characterized by a multitude of small companies, many of which were family-run and employed few or no workers outside the family. In the early 21st century, businesses with fewer than 50 employees still represented more than half of total firms, reflecting a trend that showed a decline in large production units and an increase of smaller, more-specialized ones. This trend was especially pronounced in the automobile industry, textiles, electrical goods, and agricultural, industrial, and office equipment.

Following World War II, the economy in the south was mainly dominated by the interests of the government and the public sector. The Southern Development Fund (Cassa per il Mezzogiorno), a state-financed fund set up to stimulate economic and industrial development between 1950 and 1984, met with limited success. It supported early land reform—including land reclamation, irrigation work, infrastructure building, and provision of electricity and water to rural areas—but did little to stimulate the economy. Later the fund financed development of heavy industry in selected areas, hoping that major industrial concerns might attract satellite industries and lay the foundation for sustained economic activity. Yet these projects became known as “cathedrals in the desert”; not only did they fail to attract other smaller industries, they also suffered from high absenteeism among workers. The most successful project was undertaken by Finsider, which in 1964 opened what was Europe’s most modern steelworks, in Taranto.

- POSTWAR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

The development of the Italian economy after World War II was one of the country’s major success stories. Economic reconstruction was followed by unprecedented economic growth between 1950 and 1963. Gross domestic product (GDP) rose by an average of 5.9 percent annually during this time, reaching a peak of 8.3 percent in 1961. The years from 1958 to 1963 were known as Italy’s economic miracle. The growth in industrial output peaked at over 10 percent per year during this period, a rate surpassed only by Japan and West Germany. The country enjoyed practically full employment, and in 1963 investment reached 27 percent of GDP. The success was partially due to the decision to foster free market policies and to open up international trade. From the very beginning, Italy was an enthusiastic proponent of European integration, which favoured the Italian manufacturing industry, which expanded enormously during this period. Certain products, such as Olivetti typewriters and Fiat automobiles, dominated European and world markets in just a few years. The economy slowed down after 1963 and took a downturn after the 1973 increase in petroleum prices. By the late 1980s, however, it was again prospering.

- LATER ECONOMIC TRENDS

The economy entered the mid-1980s with a healthy growth rate, which it maintained through the end of the century. However, there were serious battles to be waged: against inflation, a trade deficit, currency restrictions, and tax evasion.

Inflation reached nearly 22 percent in 1980. This was principally due to union strength in wage bargaining throughout the 1970s and a mechanism called the scala mobile, which adjusted wages to inflation on a quarterly basis for all wage and salary earners. The high degree of job security enjoyed by the Italian workforce raised production costs, which in turn contributed to inflation. Beginning with a decree in 1984 that imposed a ceiling on payments, the scala mobile was gradually dismantled (and abolished in 1992) under pressure from the employers’ association, the Confederation of Industries (Confindustria). This was reflected in a sharp fall in inflation to 12 percent in 1984 and down to 4.2 percent in 1986. However, a three-year contract signed in 1987 between Confindustria and trade unions representing all civil servants and some private industrial workers awarded pay raises over the rate of inflation, and by 1991 inflation was again up to 7 percent—3 percent higher than in Germany or France. In 2000 inflation in Italy was at 10 percent. Overall, however, the inflation rate was three times smaller throughout the 1990s than in the 1980s.

Italy’s public debt grew steadily throughout the 1980s despite a series of emergency measures designed to reduce public borrowing. By 1991 public debt exceeded GDP, and the cost of servicing it was more than $100 billion, accounting for the entire government budget deficit for the year. In 2010 Italy’s public debt still exceeded GDP.

Italy underwent currency reform in the 1980s and ’90s in an effort to come into line with the fiscal standards set by the EU. At the end of the century, Italy joined the single currency of the EU, adopting the euro in 1999.

From the late 20th century the Italian economy has been dogged by the government’s inefficient levying of direct taxes. Since the creation of the republic after World War II, the economy has relied on public loans to finance public works and enterprises, and many Italians did not start paying income tax until the 1970s. Italy also has a thriving underground economy that inevitably deprives the state of revenue. While indirect taxes, including VAT (value-added taxes), were raised several times throughout the 1980s, moves to enforce payment of direct taxes met with resistance. In 1985 a bill was introduced to curtail tax evasion among the self-employed, leading to a one-day national strike. The 1990 budget also included measures to reduce tax evasion. The names of the country’s top taxpayers are publicized annually in an attempt to encourage compliance with tax laws.

During the 1990s the annual GDP growth rates were very modest. In 2000, in response to a healthy international economy and to steps taken to improve the Italian finance system—including reduced public spending and increased taxation—the GDP grew 3 percent, its biggest increase since 1988, but the recovery would not be sustained indefinitely. In 2009 the global recession that began in 2007–08 arrived in Italy. The economy stagnated, GDP fell, and unemployment topped 10 percent. The chronic instability of the government of Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi amplified concern over Italy’s public debt, and the ratings agencies Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s downgraded the country’s credit rating in 2011. Italy found itself grouped into the acronym “PIIGS” (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, Spain), which was used to describe the countries that were at greatest risk in the euro-zone debt crisis. As Italy’s euro-zone partners constructed ever-larger financial firewalls in an effort to head off contagion, the technocratic government led by Mario Monti, who became prime minister in 2011, implemented a series of austerity measures to reduce Italy’s deficit.

Like other branches of the Italian economy, agriculture has been characterized historically by a series of inequalities, both regional and social. Until the Land Reform Acts of 1950, much of Italy’s cultivable land was owned and idly managed by a few leisured noblemen, while the majority of agricultural workers struggled under harsh conditions as wage labourers or owned derisory plots of land, too small for self-sufficiency. Agricultural workers had few rights, and unemployment ran high, especially in Calabria, where the impetus for land reform was generated. Reform entailed the redistribution of large tracts of land among the landless peasantry, thereby absorbing greater amounts of labour and encouraging more efficient land use.--->>>>>Read On.<<<<

- Resources and power

The Italian peninsula is a geologically young land formation and therefore contains few mineral resources, especially metalliferous ones. What few exist are poor in quality, scant in quantity, and widely dispersed. The meagreness of its natural resources partially explains Italy’s slow transition from an agricultural to an industrial economy, which began only in the late 19th century. The lack of iron ore and coal especially hindered industrial progress, impeding the production of steel necessary for building machines, railways, and other essential elements of an industrial infrastructure.

- IRON AND COAL

Half of Italy’s iron output comes from the island of Elba, one of the oldest geologic areas. Another important area of production is Cogne in the Alpine region of Valle d’Aosta; that deposit lies at 2,000 feet (610 metres) above sea level. Little iron-bearing ore has been produced in Italy since 1984. Coal is found in small amounts principally in Tuscany, but it is of inferior quality, and its exploitation has been almost negligible. The vast majority of Italy’s coal is imported, mostly from Russia, South Africa, the United States, and China.

- MINERAL PRODUCTION

During the late 20th century, production of almost all of Italy’s minerals steadily decreased, with the exception of rock salt, petroleum, and natural gas. In the early 1970s Italy was a major producer of pyrites (from the Tuscan Maremma), asbestos (from the Balangero mines near Turin), fluorite (fluorspar; found in Sicily and northern Italy), and salt. At the same time, it was self-sufficient in aluminum (from Gargano in Puglia), sulfur (from Sicily), lead, and zinc (from Sardinia). By the beginning of the 1990s, however, it had lost all its world-ranking positions and was no longer self-sufficient in those resources.

Fuel deposits, too, were unable to keep pace with the spiraling demands of energy-hungry industries and domestic consumers. Although domestic production figures rose throughout the late 20th century, Italy remains a net energy importer. Small amounts of oil and natural gas used to be produced in the Po valley in the 1930s, and asphalt was produced in Ragusa in Sicily. This exploitation was followed by further oil discoveries in the Abruzzo and richer amounts again in Ragusa and in nearby Gela. Natural gas is the most important natural resource in the peninsula, found mainly on the northern plain but also in Basilicata, Sicily, and Puglia.

Italy is one of the world’s leading producers of pumice, pozzolana, and feldspar. Another mineral resource for which Italy is well-known is marble, especially the world-famous white marble from the Carrara and Massa quarries in Tuscany. However, the reputation of these exceptional stones is disproportionately large when compared with the percentage of gross national product (GNP) accounted for by their exploitation.

- ENERGY

Italy’s lack of energy resources undoubtedly hindered the process of industrialization on the peninsula, but the limited stocks of coal, oil, and natural gas led to innovation in the development of new energy sources. It was the dearth of coal in the late 19th century that encouraged the pioneering of hydroelectricity, and in 1885 Italy became one of the first countries to transmit hydroelectricity to a large urban centre—from Tivoli to Rome, along a 5,000-volt line. Rapid expansion of the sector developed in the Alps (with water passing efficiently over nonporous rocks) and also in the Apennines (with less efficient transport over porous rocks). Though uneven precipitation on the peninsula marred continuing growth in hydroelectricity, it comprised a healthy slice of the country’s energy consumption by 1920. In the aftermath of World War II, more than half of Italy’s electric power was accounted for by hydroelectricity, but there was little room left for expansion, and the country was in need of energy to feed its rapid industrialization. By the 21st century, hydroelectric power, its output unable to keep pace with increasing demand, amounted to less than 20 percent of the country’s electricity production. This led to the development of thermal electricity generation fired by coal, natural gas, oil, nuclear power, and geothermal energy.

In 1949 oil was discovered off Sicily, but supplies were limited, and Italy began to rely heavily on imported oil, mainly from North Africa and the Middle East. With oil in such short supply, Italy was, not surprisingly, at the vanguard of nuclear research, and by 1965 three nuclear power stations were operating on Italian soil; a fourth opened in 1981. Nonetheless, by 1987, nuclear power accounted for only 0.1 percent of Italy’s total electricity production, and a public referendum of the same year led to the decommissioning of all four plants. The issue was revisited in the early 21st century, and a proposal to dramatically increase Italy’s nuclear power capacity was presented by the government. In a referendum held in June 2011, just months after the Fukushima disaster in Japan, the proposal was rejected. Italy remained a significant consumer of nuclear-generated power, with much of its imported electricity originating in France and Switzerland.

Natural gas has been the most significant discovery. It was first found in the 1920s, and its most important exploitation was in the Po valley. Later exploration focused on offshore supplies along the Adriatic coast. Increased reliance on imports began in the 1970s, and by the beginning of the 21st century about three-fourths of Italy’s natural gas was imported, primarily from Algeria, Russia, and the Netherlands. There are about 19,000 miles (30,000 km) of pipelines. The use of natural gas has risen at the expense of oil, which in the 1990s was the dominant energy source for electricity production in Italy. By the 21st century natural gas provided more than half of Italy’s total energy production. Overall, fossil fuels comprised some 90 percent of Italy’s total energy consumption.

- Manufacturing

- MINING AND QUARRYING

Mining is not an important sector of the Italian economy. Minerals are widely dispersed, and, unlike other industries, mining and quarrying traditionally have been more prevalent in the south than in the north. In the early 21st century, increased demand for construction materials and fertilizers led to the expansion of northern-based quarrying industries specializing in lime and chalk (for the production of fertilizers and cement, an important industry), along with coloured granites and marbles. Conversely, in the north, extraction of metalliferous minerals (such as iron ore, manganese, and zinc) declined. Nonmetalliferous minerals, including graphite, amianthus (a type of asbestos), and coal, shared a similar fate throughout Italy. As a primary fuel, coal satisfied just over one-tenth of the country’s energy demands in the early 21st century. Mining has fared badly on the islands, where it once prospered, with a decline in the extraction of sulfur in Sicily and of lead and zinc in Sardinia. Industrial minerals that remain significant are barite, cement, clay, fluorspar, marble, talc, feldspar, and pumice.

- DEVELOPMENT OF HEAVY INDUSTRY

The most remarkable feature of Italian economic development after World War II was the spectacular increase in manufacturing and, in particular, manufacturing exports. The most significant contributory factors to this growth were the Marshall Plan (1948–51), a U.S.-sponsored program to regenerate the postwar economies of western Europe; the 1952 foundation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), later under the European Federation of Iron and Steel Industries; the start in 1958 of the EEC, which contributed to the liberalization of trade; and the abundance of manpower that fueled the growth of northern industrial concerns.

The material that transformed the Italian economy with a flourish was steel. Despite the lack of mineral resources, the Italian government opted to join the ECSC at its inception, and skeptics watched as Italian steel developed so quickly that by 1980 it accounted for 21.5 percent of production in the EEC (which by then had nine members) and in western Europe. Moreover, Italy was second to West Germany among western European steel producers. Steel formed the backbone of the metallurgical and engineering industries, known as metalmeccanica. These enjoyed their heyday between 1951 and 1975, when mechanical exports rose 20-fold and the workforce employed in the industries doubled. The number of people working in the automobile industry tripled, and metallurgical exports increased 25 times. The steel industry, which declined in the last decades of the century, was privatized in 1992–97.

The main branches of metalmeccanica included arms manufacture, textile machinery, machine tools, automobiles and other transport vehicles, and domestic appliances. The automobile industry has been dominated by Fiat since the founding of the company in Turin in 1899. Milan and Brescia became the other main auto-making centres until Alfa Romeo opened its plant near Naples, leading to a decentralization of the industry. Automobile production took off in the 1950s and soared until the mid-1970s, when it began to stagnate. In the 1980s imports from Japan and an economic recession further dampened the industry, though new markets were opened in eastern Europe at the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s. In 2011 Fiat acquired a majority stake in the American auto company Chrysler, and Fiat’s involvement saw the car maker return to profitability for the first time in years. Today Italy has one of the highest numbers of cars per capita in the world.

- LIGHT MANUFACTURING

Notable large firms notwithstanding, the manufacturing sector is characterized by the presence of small and medium-size industries, which are found mainly in northeastern and north-central Italy. This area, concentrated in industrial districts within Veneto, Emilia-Romagna, and Tuscany, is referred to as the “third Italy,” to distinguish it from the “first Italy,” represented by the industrial triangle formed by the cities of Milan, Turin, and Genoa, and from the “second Italy,” which includes the Mezzogiorno. Each industrial district in the third Italy generally specializes in a particular area of light manufacturing, such as textiles or paper products, although more traditional manufacturing is also present. For instance, in Prato, Tuscany, the specialty is textile products; Sassuolo and Cento, both in Emilia-Romagna, engage in ceramic tile production and mechanical engineering, respectively; while Nogara, in Veneto, is known for wooden furniture.

Italy dominated the postwar domestic appliance market, which boomed until the first international oil crisis, in 1973, when small businesses were hard-hit by the increase in energy prices. Olivetti and Zanussi were market leaders, and Italian-produced “white goods,” such as refrigerators and washing machines, were much in demand. The textile industry has been important in Italy since the Middle Ages, when Lombardy and Tuscany were leading centres for the wool and silk industry. Other important products now include artificial and synthetic fibres, cotton, and jute yarn. Textiles and leather goods were surpassed by the metallurgical sector in the 1960s, but they remain important components of manufacturing.

The chemicals industry is one of the more recent members of the Italian industrial family. It is often categorized into primary chemicals, dominated by giant enterprises, including Edison, Eni SpA, and SNIA; secondary chemicals, made up of thousands of firms; and a third component comprising firms financed by foreign capital. From 1868 until World War I the chemical industry was restricted to products such as fertilizers and fungicides, but the oil discoveries of the 1950s opened up the vast field of petrochemicals. The discovery, too, of natural gas near Ravenna triggered the production of synthetic rubber, resins, artificial fibre, and more fertilizers. The industry boomed until the 1973 oil crisis launched a protracted slump, which rebounded somewhat in the 1980s as the sector was rationalized. During the 1990s the chemical industry was confronted with limits defined by environmental protection policies and the restructuring of small and medium-size enterprises.

The food and beverage industry is also important, in particular the traditional products olive oil, wine, fruit, and tomatoes. Additionally, the pulp and paper, printing and publishing, and pottery, glass, and ceramics industries are prominent.

- CONSTRUCTION

The housing sector was affected by three main factors following World War II: the postwar economic boom, massive rural-to-urban migration, and government incentives to the private construction sector. Approximately 500,000 homes were destroyed in the war and another 250,000 severely damaged. A period of frenzied building ensued, reaching a peak during 1961–65, when an average of 380,000 houses were built each year. Much of the building was undertaken by private companies that engaged heavily in speculative construction and paid scant regard to regulations. This led to overcrowding and a severe lack of services in peripheral urban areas. The problem was exacerbated by the migration of hundreds of thousands of southern Italians to the big northern towns in search of work.

Construction slackened during the late 1960s and ’70s as a result of economic recession, although many Italians were still living in substandard dwellings and awaiting rehousing. A 1980 earthquake in the Naples area destroyed a quarter of a million homes and resulted in a localized building boom lasting almost a decade. In the late 1990s the construction sector showed signs of recovery mainly related to investments in public works and the availability of financial incentives for residential housing. As the Italian economy declined near the end of the first decade of the 2000s, the construction industry was especially hard-hit. New building of both private homes and public works contracted sharply as financing became more difficult to secure and government funding for infrastructure improvement dried up.

- Finance

Italy’s financial and banking system has a number of unique features, although its framework is similar to that of other European countries. The Bank of Italy is the central bank and the sole bank of issue. Since the introduction of the euro in 2002, the Bank of Italy has been responsible for the production and circulation of euro notes in accordance with EU policy. Execution of monetary policy is vested in the Interministerial Committee for Credit and Savings, headed by the minister for the economy and finance. In practice, the Bank of Italy enjoys wide discretionary powers (within the constraints of the Maastricht Treaty and other agreements that govern the euro zone) and plays an important role in euro-zone economic policy making. The bank’s primary function also includes the control of credit.

There are three main types of banking and credit institutions. First, there are the commercial banks, which include three national banks, several chartered banks, popular cooperative banks—whose activities do not extend beyond the provincial level—and ordinary private banks. Second, there is a special category of savings banks organized on a provincial or regional basis. Finally, there are the investment institutions, which collect medium- and long-term funds by issuing bonds and supply medium- and long-term credit for industry, public works, and agriculture. The 1990 Banking Act reduced the level of public ownership of banks and facilitated the raising of external capital. All remaining controls on capital movements were also lifted, enabling Italians to bank unlimited amounts of foreign capital in Italy.

There are many institutes of various kinds supplying medium- and long-term credit. These special credit institutions have as their primary aim the increase of the flow and the reduction of the cost of development finance, either to preferential areas or to priority sectors (for example, agriculture or research) or to small and medium-size business. In addition to this network of special credit institutions, there is a subsystem of credit under which the government shoulders part of the interest burden.

The bond market in Italy is well-developed. Mainly as a result of the special structure of government-sponsored institutions for development finance and subsidized interest rates, the growth of the capital market and stock exchanges was far less important than in other Western industrialized countries. The development of the stock exchange in Italy was initially hampered by the archaic structure and rules of the markets and by tax problems connected with the registration of shares. More recently, however, the market was modernized; the Borsa Italiana, which manages the stock exchange, became operational in 1998.

- Trade

Italy has a great trading tradition. Jutting out deeply into the Mediterranean Sea, the country occupies a position of strategic importance, enhancing its trading potential not only with eastern Europe but also with North Africa and the Middle East. Italy has historically maintained active relations with eastern European countries, Libya, and the Palestinian peoples. These links have been preserved even at times of great political tension, such as during the Cold War and the Persian Gulf War of 1991. Membership in the EC from 1957 increased Italy’s potential for trade still further, giving rise to rapid economic growth. However, from that time, the economy was subject to an ever-widening trade deficit. Between 1985 and 1989 the only trading partner with which Italy did not run a deficit was the United States. Italy began showing a positive balance again in the mid-1990s. Trade with other EU members accounts for more than half of Italy’s transactions. Other major trading partners include the United States, Russia, China, and members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Italy’s trading strength was traditionally built on textiles, food products, and manufactured goods. During the second half of the 20th century, however, products from Italy’s burgeoning metal and engineering sector, including automobiles, rose to account for a majority share of the total exports, which it still retains; they are followed by the textiles, clothing, and leather goods sector. The most avid customers of Italian exports are Germany, France, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Spain.

Italy’s main imports are metal and engineering products, principally from Germany, France, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Chemicals, vehicle, and mineral imports are also important commodities. Italy is a major importer of energy, with much of its oil supply coming from North Africa and the Middle East.

Membership in the EEC was the most beneficial economic factor in Italian trade during the post-World War II period. The later accession of Greece, Spain, and Portugal to the EEC created stiff competition for Mediterranean agricultural products, especially fruit, wine, and cooking oil. At the beginning of the 21st century, however, the expanded EU and the weakness of the new euro currency allowed for export growth in Italy. As the euro reached and ultimately surpassed parity with the U.S. dollar, this advantage was lost, and for the first decade of the 21st century Italy maintained a negative trade balance.

- Services and tourism

- BUSINESS SERVICES

The service sector is one of the most important in Italy in terms of the number of people employed. If the definition extends to cover tourism, the hotel industry, restaurants, the service trades, transport and communications, domestic workers, financial services, and public administration, well over half of the workforce operates in the sector. A fully accurate measure is impossible, however, because of the existence of a burgeoning black market.

A plentiful supply of labour has nourished the service sector, especially in the large urban areas, since the 1950s. This labour came initially from rural areas of northern Italy such as Veneto; later the Italian peasantry from the Mezzogiorno migrated north; and more recently immigrants from less-developed countries—many of whom work for low wages, without job security, and under substandard work conditions—have filled low-grade urban service jobs. High-level service jobs include those involved with information technologies, which are used by one-third of Italian business. Factors that have contributed to the growth of the service sector include the rise in the standard of living in Italy and Europe in general, leading to an increase in mobility, financial transactions, business, demand for leisure activities, and tourism.

- TOURISM

Italy is renowned as a tourist destination; it attracted more than 40 million foreign visitors annually in the early 21st century. Conversely, less than one-fifth of Italians take their holidays abroad. The tourist industry in Italy experienced a decline from 1987 onward, including a slump during the Persian Gulf War and world recession, but it rebounded in the 1990s, posting gains in the number of overseas and domestic tourists. In addition, the Jubilee celebrations promoted by the Roman Catholic Church in 2000 to mark the advent of its third millennium attracted millions of tourists to Rome and its enclave, Vatican City, the seat of the church.

The tourist industry has flourished under both national and international patronage. The most popular locations, apart from the great cultural centres of Rome, Florence, Venice, and Naples, are the coastal resorts and islands or the Alpine hills and lakes of the north; the Ligurian and Amalfi rivieras; the northern Adriatic coast; the small islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea (Elba, Capri, and Ischia); the Emerald Coast of Sardinia; Sicily; Gran Paradiso National Park and the Dolomites; and Abruzzo National Park.

- Labour and taxation

Women constitute about two-fifths of the labour force, though they are more likely to take on fixed-term and part-time employment than men. The activity rate of male employment is consistent throughout Italy, but females have a much lower rate of participation in the south.

Because of the scala mobile, which adjusted wages to inflation, Italian workers benefited from high job security for decades after World War II. Beginning in the 1980s, though, as the government moved to get inflation under control, the scala mobile came under attack and was eventually terminated in 1992.

The strength of trade unions was in decline by the end of the 20th century, but large general strikes were not uncommon. The right to strike is guaranteed by the constitution and remains a very potent weapon in the hands of the trade unions. Three major labour federations exist, each closely tied to different political factions: the General Italian Confederation of Labour (Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro; CGIL), which is tied to the left; the Italian Confederation of Workers’ Unions (Confederazione Italiana di Sindicati Liberi; CISL), with ties to the Catholic movement; and the Italian Labour Union (Unione Italiana del Lavoro; UIL), related to the secular parties. A number of independent unions are also active, especially in the public service sector. They increasingly challenge the monopoly of the three confederations on national contractual negotiations and are quite militant.

The government has undertaken reforms in tax collection. Historically, it has been unsuccessful in gathering income taxes with consistency, in part because of tax evasion and a black market on goods.

- Transportation and telecommunications

- WATER TRANSPORT

Water transport was the first important means of linking Italy with its Mediterranean trading partners, even though its only navigable internal water is the Po River. At the time of unification in the 19th century, the ports of Venice, Palermo, and Naples were of great significance, and the Italian merchant fleet was preeminent in the Mediterranean Sea. The 4,600 miles (7,400 km) of Italian coastline are punctuated by many ports, and a large majority of imports and exports arrive and leave the country by sea. The principal dry-cargo ports are Venice, Cagliari, Civitavecchia, Gioia Tauro, and Piombino, while those handling chiefly petroleum products are Genoa, Augusta, Trieste, Bari, and Savona. Naples and Livorno handle both types of cargo. Half of the commercial port traffic is concentrated on only one-tenth of the coastline. The industries of Piedmont and Lombardy make heavy demands on the maritime outlets, particularly Genoa, which is the most extensive and important Italian port but which has great difficulty expanding because of the mountains surrounding it.

- RAIL TRANSPORT

The main period of railway construction was about the time of unification, from 1860 until 1873. The heavy costs involved in laying down the infrastructure caused the government to sell off its stake in 1865. By this time the networks serving Milan, Genoa, and Turin in the north were well-developed. These were followed by links through the Po valley to Venice; to Bari, along the Adriatic coast; down the Tyrrhenian coast, through Naples, to Reggio di Calabria; and from Rome to the Adriatic cities of Ancona and Pescara. The Sicilian and Sardinian networks also were built. A period of rationalization and modernization followed in 1905 when the network was renationalized; building of new rail lines continued throughout the 20th century. An exceptional feature was the early electrification of the lines, many of which ran through long tunnels and were ill-suited to steam power. This modernization was due to Italy’s early development of hydroelectricity.

Although the rail network is well distributed throughout the peninsula, there are important qualitative differences between its northern and southern components. The north enjoys more frequent services, faster trains, and more double track lines than the south. Compared with other European networks, the Italian trains carry little freight but many passengers, partly because the railways failed to keep pace with the rapid rate of industrialization after World War II, while the passenger lines were made inexpensive through government subsidies. Eighty percent of the rail network was controlled by the state via Ferrovie dello Stato (“State Railways”) before it was privatized in 1992.

The Italian railways are connected with the rest of Europe by a series of mountain routes, linking Turin with Fréjus in France, Milan with Switzerland via the Simplon Tunnel, Verona to Austria and Germany via the Brenner Pass, and Venice to eastern Europe via Tarvisio. In the late 20th century routes were expanded, extended, and modernized, including the addition of high-speed lines and computerized booking and freight control systems. The railway network extends some 10,000 miles (16,000 km).

- ROAD TRANSPORT

The Italian road network is subdivided into four administrative categories—express highways (autostrade) and national, provincial, and municipal roads (strade statali, strade provinciali, and strade comunali, respectively). Road construction in Italy flourished between 1955 and 1975. Between 1951 and 1980, surfaced roads, excluding highways and urban streets, increased by 72 percent to cover more than 183,000 miles (295,000 km). Automobile sales increased faster than in any other western European economy during this period. Much of this was due to mass production of cheap models by Fiat. Road construction in the south particularly benefited from funds released by the Southern Development Fund.

- ROAD TRANSPORT

The Italian road network is subdivided into four administrative categories—express highways (autostrade) and national, provincial, and municipal roads (strade statali, strade provinciali, and strade comunali, respectively). Road construction in Italy flourished between 1955 and 1975. Between 1951 and 1980, surfaced roads, excluding highways and urban streets, increased by 72 percent to cover more than 183,000 miles (295,000 km). Automobile sales increased faster than in any other western European economy during this period. Much of this was due to mass production of cheap models by Fiat. Road construction in the south particularly benefited from funds released by the Southern Development Fund.

Government and Society of Italy

Constitutional framework

CONSTITUTION OF 1948

The Italian state grew out of the kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont, where in 1848 King Charles Albert introduced a constitution that remained the basic law, of his kingdom and later of Italy, for nearly 100 years. It provided for a bicameral parliament with a cabinet appointed by the king. With time, the power of the crown diminished, and ministers became responsible to parliament rather than to the king. Although the constitution remained formally in force after the fascists seized power in 1922, it was devoid of substantial value. After World War II, on June 2, 1946, the Italians voted in a referendum to replace the monarchy with a republic. A Constituent Assembly worked out a new constitution, which came into force on January 1, 1948.

The constitution of Italy has built-in guarantees against easy amendment, in order to make it virtually impossible to replace it with a dictatorial regime. It is upheld and watched over by the Constitutional Court, and the republican form of government cannot be changed. The constitution contains some preceptive principles, applicable from the moment it came into force, and some programmatic principles, which can be realized only by further enabling legislation.

The constitution is preceded by the statement of certain basic principles, including the definition of Italy as a democratic republic, in which sovereignty belongs to the people (Article 1). Other principles concern the inviolable rights of man, the equality of all citizens before the law, and the obligation of the state to abolish social and economic obstacles that limit the freedom and equality of citizens and hinder the full development of individuals (Articles 2 and 3).

Many forms of personal freedom are guaranteed by the constitution: the privacy of correspondence (Article 15); the right to travel at home and abroad (Article 16); the right of association for all purposes that are legal, except in secret or paramilitary societies (Article 18); and the right to hold public meetings, if these are consistent with security and public safety (Article 17). There is no press censorship, and freedom of speech and writing is limited only by standards of public morality (Article 21). The constitution stresses the equality of spouses in marriage and the equality of their children to each other (Articles 29 and 30). Family law has seen many reforms, including the abolition of the husband’s status as head of the household and the legalization of divorce and abortion. One special article in the constitution concerns the protection of linguistic minorities (Article 6).

The constitution establishes the liberty of all religions before the law (Article 8) but also recognizes the special status granted the Roman Catholic Church by the Lateran Treaty in 1929 (Article 7). That special status was modified and reduced in importance by a new agreement between church and state in 1985. Because of these changes and the liberal tendencies manifested by the church after the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, religion is much less a cause of political and social friction in contemporary Italy than it was in the past.

The constitution is upheld by the Constitutional Court, which is composed of 15 judges, of whom 5 are nominated by the president of the republic, 5 are elected by parliament, and 5 are elected by judges from other courts. Members must have certain legal qualifications and experience. The term of office is nine years, and Constitutional Court judges are not eligible for reappointment.

The court performs four major functions. First, it judges the constitutionality of state and regional laws and of acts having the force of law. Second, the court resolves jurisdictional conflicts between ministries or administrative offices of the central government or between the state and a particular region or between two regions. Third, it judges indictments instituted by parliament. When acting as a court of indictment, the 15 Constitutional Court judges are joined by 16 additional lay judges chosen by parliament. Fourth, the court determines whether or not it is permissible to hold referenda on particular topics. The constitution specifically excludes from the field of referenda financial decisions, the granting of amnesties and pardons, and the ratification of treaties.

THE LEGISLATURE

Parliament is bicameral and comprises the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. All members of the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house) are popularly elected via a system of proportional representation, which serves to benefit minor parties. Most members of the Senate (the higher chamber) are elected in the same manner, but the Senate also includes several members appointed by the president and former presidents appearing ex officio, all of whom serve life terms.

In theory, the Senate should represent the regions and in this way differ from the lower chamber, but in practice the only real difference between them lies in the minimum age required for the electorate and the candidates: 18 and 25 years, respectively, for deputies and 25 and 40 for senators. Deputies and senators alike are elected for a term of five years, which can be extended only in case of war. Parliamentarians cannot be penalized for opinions expressed or votes cast, and deputies or senators are not obligated to vote according to the wishes of their constituents. Unless removed by parliamentary action, deputies and senators enjoy immunity from arrest, criminal trial, and search. Their salary is established by law, and they qualify for a pension.

Both houses are officially organized into parliamentary parties. Each house also is organized into standing committees, which reflect the proportions of the parliamentary groups. However, the chairmanship of parliamentary committees is not the exclusive monopoly of the majority. Besides studying bills, these committees act as legislative bodies. The parliamentary rules have followed the United States’ pattern and have given the standing committees extensive powers of control over the government and administration. All these features explain why the government has a limited ability to control the legislative agenda and why parliamentarians are often able to vote contrary to party instructions and to avoid electoral accountability. The abolition of secret voting on most parliamentary matters at the end of the 1980s did not significantly change this situation.

Special majorities are required for constitutional legislation and for the election of the president of the republic, Constitutional Court judges, and members of the Superior Council of the Magistrature. The two houses meet jointly to elect and swear in the president of the republic and to elect one-third of the members of the Superior Council of the Magistrature and one-third of the judges of the Constitutional Court. They may also convene to impeach the president of the republic, the president of the Council of Ministers, or individual ministers.

Each year, the annual budget and the account of expenditure for the past financial year are presented to parliament for approval. The budget, however, does not cover all public expenditure, nor does it include details of the budgets of many public bodies, over which, therefore, parliament has no adequate control. International treaties are ratified by means of special laws.

The most important function of parliament is ordinary legislation. Bills may be presented in parliament by the government, by individual members, or by bodies such as the National Council for Economy and Labour, various regional councils, or communes, as well as by petition of 50,000 citizens of the electorate or through a referendum. Bills are passed either by the standing committees or by parliament as a whole. In either case, the basic procedure is the same. First, there is a general debate followed by a vote; then, each of the bill’s separate articles is discussed and voted on; finally, a last vote is taken on the entire bill. All bills must be approved by both houses before they become law; thus, whenever one house introduces an amendment to the draft approved by the other house, the latter must approve the amended draft.

The law is then promulgated by the president of the republic. If the president considers it unconstitutional or inappropriate, it is remanded to parliament for reconsideration. If the bill is, nevertheless, passed a second time, the president is obliged to promulgate it. The law comes into force when published in the Gazzetta Ufficiale.

THE PRESIDENTIAL OFFICE

The president of the republic is the head of state and serves a term of seven years. The prosecutorial immunity that applies to members of the legislature does not extend to the chief executive, and the president can be impeached for high treason or offenses against the constitution, even while in office. The president is elected by a college comprising both chambers of parliament, together with three representatives from every region. The two-thirds majority required guarantees that the president is acceptable to a sufficient proportion of the populace and the political partners. The minimum age for presidential candidates is 50 years. If the president is temporarily unable to carry out his functions, the president of the Senate acts as the deputy. If the impediment is permanent or if it is a case of death or resignation, a presidential election must be held within 15 days.

Special powers and responsibilities are vested in the president of the republic, who promulgates laws and decrees having the force of law, calls special sessions of parliament, delays legislation, authorizes the presentation of government bills in parliament, and, with parliamentary authorization, ratifies treaties and declares war. However, some of these acts are duties that must be performed by the president, whereas others have no validity unless countersigned by the government. The president commands the armed forces and presides over the Supreme Council of Defense and the Superior Council of the Magistrature.

Presidents may dissolve parliament either on their own initiative (except during the last six months of their term of office), having consulted the presidents of both chambers, or at the request of the government. They may appoint 5 lifetime members of the Senate, and they appoint 5 of the 15 Constitutional Court judges. They also appoint the president of the Council of Ministers, the equivalent of a prime minister. Whenever a government is defeated or resigns, it is the duty of the president of the republic, after consulting eminent politicians and party leaders, to appoint the person most likely to win the confidence of parliament; this person is usually designated by the majority parties, and the president has limited choice.

THE GOVERNMENT

The government comprises the president of the Council of Ministers and the various other ministers responsible for particular departments. Ministerial appointments are negotiated by the parties constituting the government majority. Each new government must receive a vote of confidence in both houses of parliament within 10 days of its appointment. If at any time the government fails to maintain the confidence of either house, it must resign. Splits in the coalition of two or more parties that had united to form a government have caused most of the resignations of governments.

According to the constitution, the president of the Council of Ministers is solely responsible for directing government policies and coordinating administrative policy and activity. In reality, the president tends to function as a negotiator between government parties and factions. The government can issue emergency decree laws signed by the president of the republic, provided such laws are presented to parliament for authorization the day they are issued and receive its approval within 60 days. Without such approval, they automatically lapse. The government and, in certain cases, individual ministers issue administrative regulations and provisions, which are then promulgated by presidential decree.

- Regional and local government

The republic is divided into regions (regioni), provinces (province), and communes (comuni). There are 15 ordinary regions and an additional 5 to which special autonomy has been granted. The regions with ordinary powers are Piedmont, Lombardy, Veneto, Liguria, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria, Marche, Lazio, Abruzzo, Molise, Campania, Puglia, Basilicata, and Calabria. Italy can thus be considered a regional state. The modern regions correspond to the traditional territorial divisions. The powers of the five special regions—which are Sicily, Sardinia, Trentino–Alto Adige, Friuli–Venezia Giulia, and Valle d’Aosta—derive from special statutes adopted through constitutional laws.

The organs of regional government are the regional council, a popularly elected deliberative body with power to pass laws and issue administrative regulations; the regional committee, an executive body elected by the council from among its own members; and the president of the regional committee. The regional committee and its president are required to resign if they fail to retain the confidence of the council. Voting in the regional councils is rarely by secret ballot.

Participation in national government is a principal function of the regions: regional councils may initiate parliamentary legislation, propose referenda, and appoint three delegates to assist in presidential elections, except for the Valle d’Aosta region, which has only one delegate. With regard to regional legislation, the five special regions have exclusive competence in certain fields—such as agriculture, forestry, and town planning—while the ordinary regions have competence over them within the limits of fundamental principles established by state laws.

The legislative powers of both special and ordinary regions are subject to certain constitutional limitations, the most important of which is that regional acts may not conflict with national interests. The regions can also enact legislation necessary for the enforcement of state laws when the latter contain the necessary provisions. The regions have administrative competence in all fields in which they have legislative competence. Additional administrative functions can be delegated by state laws. The regions have the right to acquire property and the right to collect certain revenues and taxes.

The state has powers of control over the regions. The validity of regional laws that are claimed to be illegal can be tested in the Constitutional Court, while those considered inexpedient can be challenged in parliament. State supervisory committees presided over by government-appointed commissioners exercise control over administrative acts. The government has power to dissolve regional councils that have acted contrary to the constitution or have violated the law. In such an event, elections must be held within three months.

The organs of the commune, the smallest local government unit, are the popularly elected communal council, the communal committee, or executive body, and the mayor. The communes have the power to levy and collect limited local taxes, and they have their own police, although their powers are much inferior to those exercised by the national police. The communes issue ordinances and run certain public health services, and they are responsible for such services as public transportation, garbage collection, and street lighting. Regions have some control over the activity of the communes. Communal councils may be dissolved for reasons of public order or for continued neglect of their duties.